In Colombia, there is a gap in the quality of education between urban and rural households, which is caused by multiple factors. On the one hand, rural families have, on average, less education, and it is also more common for children growing up in rural areas to spend more time working. On the other hand, there are fewer educational centers in rural areas, and those that do exist tend to be smaller and have fewer resources.

Geographic isolation could help explain the disadvantage faced by rural students. It is known, for example, that being close to cities increases productivity, not only because of greater access to markets and information, but also because of the State's greater administrative capacity, which translates into more and better public services. In education, lower test scores in the Prueba SABER in remote regions suggest that this is also the case. A relevant question is whether this is associated with distance to population centers or other factors.

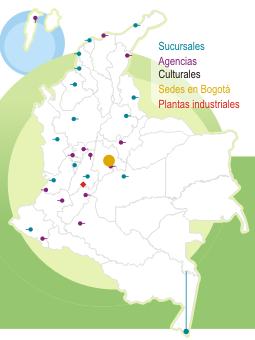

A recent study by Banco de la República (the Central Bank of Colombia) on geographic isolation and rural education in Colombia conducted by Leonardo Bonilla and Erika Londoño addresses this question. The authors begin by calculating the travel time between rural schools and the respective municipal seats where the mayor's office is located and departmental capital cities where the Departments of Education in charge of providing education services in small municipalities operate.

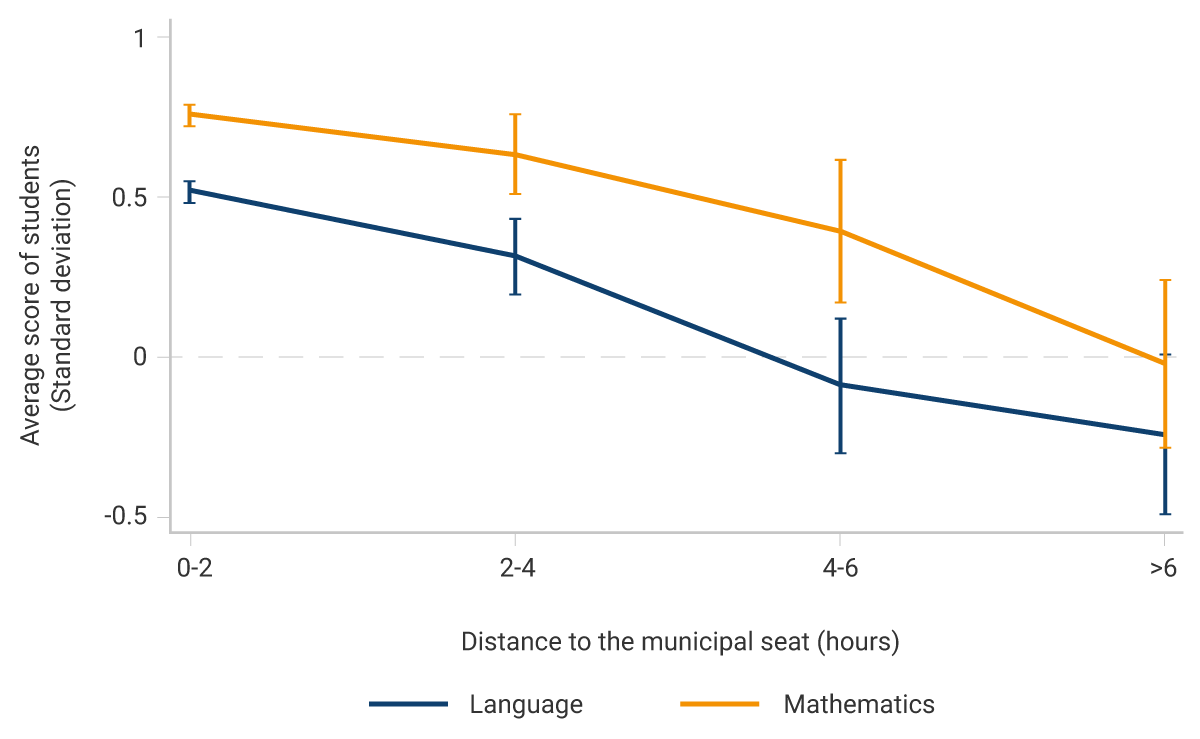

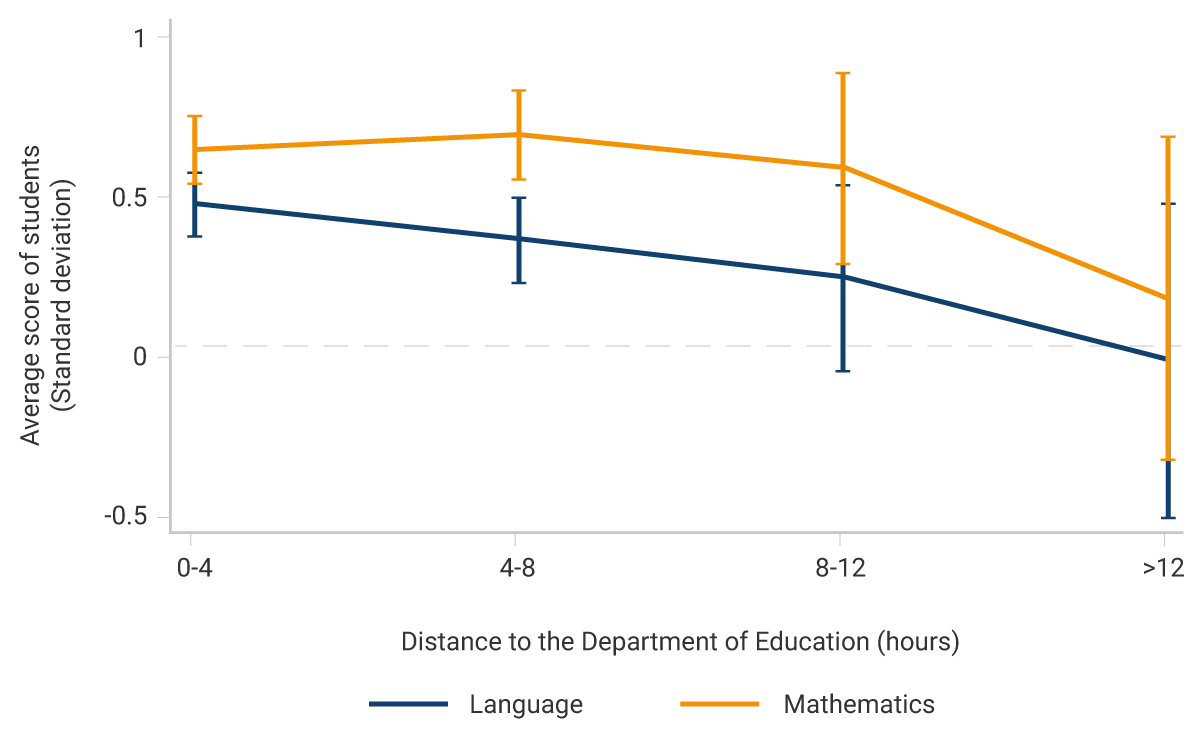

As previous studies have documented, learning, as measured by SABER 3 and 5 elementary standardized test scores, decreases as the school moves away from the municipal seat and the departmental capital city (Graph 1).

Graph 1. Distance and Performance on the Saber 3 and 5 Tests

To measure how much of this gap is explained by geographic isolation, the authors estimate an econometric model that compares the performance on the SABER tests of schools that are similar in all respects except distance to the respective local governments1. Results suggest that both the distance to the municipal seat and the distance to the Department of Education have a negative and significant effect on learning. This confirms that geographic isolation plays an essential role in urban-rural educational gaps.

The authors also exhibit that the negative association between educational test scores and the distance of schools from population centers is due to significant differences in the school system’s inputs, especially as regards teaching staff. Indeed, in more remote schools, teachers are more likely to have temporary contracts and a lower level of academic training.

This is not a new problem. Since 2009, the Ministry of Education has had an incentive program to attract and retain teachers and executives in the country’s most remote areas. Currently, 60% of teachers in rural institutions in the country receive this subsidy. The results of the study show that the relationship between distance and learning is mainly explained by schools classified as difficult to access and that taking such incentives into account in the estimates does not mitigate the disadvantages of isolation. This suggests that the impact of the program is limited. This could be partly explained by the design of incentives. Indeed, all teachers working in schools classified as difficult to access receive the same bonus, regardless of the distance and difficulty of access to municipal seats and departmental capital cities. The results of this study suggest the desirability of remuneration policies that consider the isolation of schools to improve the quality of rural education.

1 Specifically, spatial discontinuous regressions are estimated that compare schools located near the border between two municipalities, and that differ mainly in the distance to the respective municipal seats or departments of education.